Twelve days after the beginning of the uprising, the New York Times’ South African correspondent, Michael Kaufman, after gathering eyewitness reports, filed a report with America’s, and the world’s, most eminent newspaper.

I wanted to share the report to note the differences between how the event was initially reported and how it is remembered today.

Let me preface this.

The Nationalist government, since Verwoerd, had pursued a policy of ‘grand apartheid’, in which the regime would recognise autonomous states within South Africa based on ethnicity, so as to allow the various ethnic ‘nations’ to pursue their own development.

There was a great hypocrisy at the heart of this, because South African big business, notably its cosmopolitan mining interests, still wanted cheap black labour in the so-called white areas.

This meant that black workers were housed in conditions far inferior to those available to white South Africans in the big cities, and even though the economy depended on their labour, they were not regarded as true citizens in those areas. (Think of the name Soweto. It is just an abbreviation for South-West Townships.)

And second of all, the land devoted to the seven or eight nations, was not really generous enough to make the system workable. Verwoerd had restricted investment in the areas on the basis that white capital would erode African self-reliance.

That said, the government did commit £75 million, which pro-worker British newspaper, The Guardian, compared favourably with the £14 million Britain had given in aid to their protectorates in Southern Africa. It is also notable that at the time Mandela himself regarded the estabishment of said homelands as a positive development.

Massive black population growth in the cities, which had begun under Verwoerd, had also exacerbated the contradiction. To that end, Prime Minister John Vorster had paused any increases in white welfare spending to increase black welfare spending (which remained less per capita). A prime example of this impulse was the ever-growing Baragwanath Hospital in Soweto, said to be the largest hospital in the southern hemisphere.

You can read more on the history of apartheid below:

What is a Sensitive Young Man Meant to Make of the History of Apartheid?

This essay forms part of a series for my paid subscribers on the liberal myths that have shaped modern anarcho-tyranny:

This tension from these contradictions would ultimately explode in Soweto 49 years ago today, not from workers, however, but from the youth, who would launch a protest at the edict of the government that half their school subjects would need to be taught in Afrikaans.

I turn now to the New York Times.

Look for the following highlights as you read it:

A week before the riots, a teacher had been stabbed.

Part of the march was planned to gather the support of high school students, who were not taught in Afrikaans.

The riots began on a bridge, where, after having rocks thrown at them, the police attempted to disperse the crowd with tear gas. The crowd surged towards them instead. That is when the shooting began.

In the aftermath, a body of a black policeman hacked to death was discovered in his car, Indian doctors had to run for their lives from Soweto clinics, and two Jewish social workers were murdered.

Liquor stores and shops were looted and banks set on fire.

Does the report justify the actions of the police. No. But it does provide some context.

It is worth reading in full below.

Witnesses Tell What They Saw When Riots Came to Soweto

By Michael T. Kaufman Special to The New York Times

June 28, 1976

JOHANNESBURG, June 27—Sometime between 7:30 and 9 A.M. on Wednesday, June 16, a march of schoolchildren in the black township of Soweto turned into one of the worst racial riots in South African history.

Many people saw it happen. Few are willing to talk about what they saw. Still, from the accounts of witnesses whose descriptions were given under guarantees of anonymity, a picture emerges of what took place on that chilly morning that began with songs and ended with shots.

The scene was set the day before. A group of perhaps a hundred elementary and junior high school students gathered in Soweto, the largest of the townships where urban blacks are compelled to live, to plan a march for the next morning that would continue a fiveweek protest against the mandatory use of the Afrikaans language in teaching such subjects as mathematics and science.

Since Soweto schools are open only to those who can afford books and uniforms, it is not uncommon to have students aged 16. 17 and even 18 in the lower grades; and most of those at the meeting were reportedly in that age group.

Protest Was Developing

The language protest had been building, and there were boycotts in several schools. A week earlier a teacher was stabbed. A member of the Soweto Council, a black group, had warned two days before the riots that unless the authorities dealt quickly with the language issue, the protest could lead to violence.

However, there was little awareness of the problem among the white South Africans whose newspapers hardly mentioned it. Certainly the governing white minority of 2.5 million did not view the Soweto protest as comparable to the organized campaign of burning identification cards that led to rioting in Sharpeville in 1960, in which 72 blacks were killed by police gunfire.

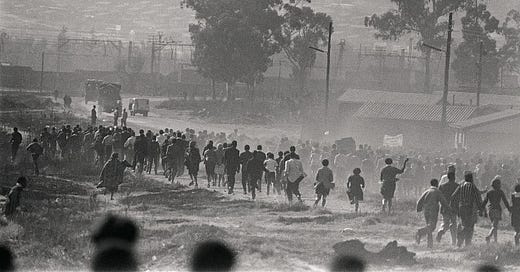

In any case the June 15 meeting in Soweto ended peacefully. The next morning, as pu pils in their school blazers left their homes, some carried handwritten signs declaring, “Afrikaans is for Boers, not Africans.” As older students moved from the dusty, treeless, unnamed back streets to thee, major thoroughfares they were joined by 8‐ and 9‐year‐olds. They were heading toward a sports stadium, where they planned to hold a rally.

According to witnesses, the marching students raised their fists in the salute of what is called the black power movement, more an attitude among the 18 million blacks than a political organization. Some sang forbidden anthems of the African National Congress the outlawed nationalist group. One man, who estimated the crowd at several thousand, said none of the youths he saw were carrying sticks or stones. Photographs of the marchers before trouble erupted showed neatly dressed boys and girls smiling or laughing.

Seeking Some Recruits

According to several witnesses, the marchers’ route took them through a section of Seweto called Phefani, heading for the adjoining neighborhood of Orlando East, where the stadium is. Some marchers said they thought they were going to stop at the Orlando High School to enlist its students in the protest. High schools in Soweto do not use Afrikaans, the language of the governing Nationalists, in instruction.

Some students said they were particularly angered by the principal of the Orlando school, who had recently organized a “boys on the border fund,” to which pupils were asked to contribute money, for the recreation of South African soldiers serving in South‐West Africa in a campaign against guerrillas.

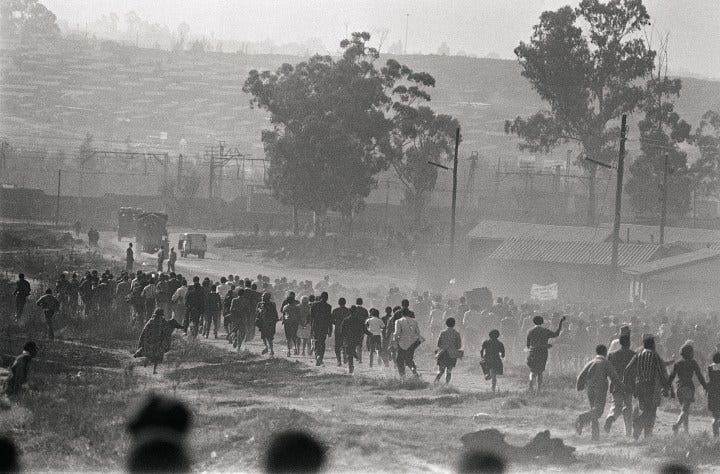

Shortly after 8 A.M. the marchers, apparently the main body of the students, crossed a railroad bridge and entered Orlando, where they were stopped by policemen. According to a number of witnesses, it was there that the riot started, though there may have been smaller incidents elsewhere in the vast Soweto area, where more than a million people live.

A black office worker said he saw the confrontation between the marchers and the police from a distance of several hundred yards. There were a few minutes of what seemed to him to be quiet discussion. A few stones were then thrown from the back ranks of the students, he related and tear gas was fired by the police but the crowd did not immediately disperse. Instead there was a surge forward.

At that point, the witness said, shots were heard. He said he saw policemen using sidearms and some students fell, but most ran away. The witness, who had by this time gone to stand with a group of people in front of a police station, heard that a boy named Hector Peterson had been shot to death.

While the witness stood near the police station he heard a black woman say that it was a shame that the policemen had fired at children. The remark was overheard by a white officer, who, the witness said, or dered black policemen to arrest the woman.

In an account of the rioting later in the day, James T Kruger, Minister of Justice said the police had exercised the “greatest measure of self-control” and had fired only when their lives were endangered. He also said that the police had fired only after black mobs had hacked black and white government employees to death. However, it was not until nearly 11 am, three hours after witnesses reported the first police fire at the students, that the body of a black policeman was found in his car.

On Friday. Mr. Kruger, at a news conference for the foreign press, said the march had caught the police by surprise. Three‐man patrols were dispatched to learn what was happening, he said, and 30 black policemen, only some of whom were armed, were sent with a white officer to head off the largest group of marchers.

The police tried to talk with the leaders at the head of the march, Mr. Kruger asserted, and tear gas was fired, but because of the openness of the terrain it proved ineffective.

The leader of the marchers. whom Mr. Kruger identified as not being a student. “took up a very threatening attitude and he was shot.”

The Minister, saying he was certain that if shots had not been fired the riot would have developed in any case, noted that arson attacks broke out simultaneously in widely separated areas of Soweto.

The timing of the shootings will undoubtedly be the major focus of the judiciary inquiry ordered a day after the riots flared. However, wittnesses, all of whom were concentrated near the area where young Peterson died and all of whom profess varying degrees of sympathy for the marchers, insist that the attacks on Government property and Government workers followed rather than preceded the initial police shooting.

The witnesses say that as news of the boy's death spread, the students broke into groups and began attacks on schools, offices and cars believed to belong to whites. One man told of seeing Indian doctors from a neighborhood clinic running for safety pursued by a mob.

It was in this outburst of rage that two white social workers were killed. One of them was a sociologist named Melville Edelstein whose doctoral dissertation had warned of the latent rage of educated urban blacks toward Afrikaans.

Bank Was Burned

During the early hours a Barclays Bank branch was burned and the offices of the agency administering black affairs were ransacked and gutted. A man told of seeing youths demanding to buy kerosene at a gasoline station; when the owner refused they reportedly beat him and set the station on fire.

Some witnesses said they had heard that stores and schools had been targeted for attack. Schools where teachers and principals had endorsed the language protest were not burned. One of the first stores to be burned, one witness related, was the Verwoerd Shop, named after the assassinated Prime Minister.

The store was owned by a black man, but most of the others belonged to Indians, Chinese and colored people of mixed ethnic stock. In the last few years the Government has allowed only blacks to open businesses in their townships, but some nonblacks who have been there for many years were allowed to stay. Many of their shops are in an area called White City, which was particularly hard hit by looters.

As the rioting continued into the night of the 16th, 5,000 policemen and police reservists were in and around Soweto, which lies 10 miles west of Johannesburg. They were armed with shotguns and submachine guns but not gasmasks or helmets.

Witnesses said that by noon soldiers rode through the township on open trucks firing at youths, who scattered.

By early afternoon telephone communication was cut off, train service stopped and heavily manned checkpoints were set up on the few roads leading to the community.

The witnesses generally agreed that the students lost control of the situation late in the day to older people and to the tsotsis, as members of gangs of young hoodlums are known in Zulu slang. The state-run liquor stores became the targets, and the witnesses said many people could be seen running through the streets with beer and whiskey. Many were reportedly drunk.

Late on June 17 the police and health authorities stopped reporting the fatality toll. At that time the number of officially reported dead stood at 41, including the two whites.

By the 18th the riots began spreading to other townships, and Prime Minister John Vorster, then preparing to leave for his meeting with Secretary of State Henry A. Kissinger in Germany, announced that the Government had given instructions to the police “to maintain law and order at all costs.”

According to witnesses, the statement was followed by greater shows of force by the police, particularly in Alexandra Township, the only black area that is close to white residential neighborhoods. As. the Soweto disorders were lessening, violence flared in townships northward to Pretoria, but it did not rage as long as in Soweto.

The official death toll, which Thursday was reported as 140, was raised to 176 on Friday by the Minister of Justice. Mr. Kruger said the number included two whites and 12 children. He said 1,139 people had been wounded and 1,298 arrested.

UN. Figures Denied

He emphatically denied assertions he said were made in New York by the United Nations Committee on Apartheid that more than a thousand blacks were killed.

Some in Soweto feel that the officially reported toll here is somewhat low, though they say that the United Nations figure is much too high. One man said he believed he saw 80 bodies in Soweto, 20 of them in a single place, near the Moroka stores, where they had apparently been shot as looters.

Three days ago the black morgue here reported holding the unclaimed bodies of 93 riot victims. This was a day after a black undertaker reported he had removed eight bodies and other undertakers had claimed others. The morgue reported that those who died of stab wounds were still awaiting autopsies.

The mood in Johannesburg, which had been noticeably tense until last weekend, is quite calm. Whites and blacks pass each other on the street with no looks of hatred or suspicion. In elevators whites and blacks make small talk without mention of Soweto. In private, however, whites say that the riots indicate a significant rise in black militancy.

“This is much different than Sharpeville,” a white university student commented. That incident in a township 35 miles from here, he said, was a result of an organized drive to protest apartheid by having people burn their identity cards, known as pass books. The authorities were able to arrest the organizers and while the world expressed outrage, the protest at home stopped. In Soweto the student said, anger and defiance have lingered.

A young black salesman said that among his friends in Soweto—he said they were not activists—the mood was not just sorrow and anger but pride as well. “There is a feeling that Soweto has showed that we are not quite so docile as the whites believed,” he explained.

To learn more about South Africa, read my book Rage and Love: A Memoir of White South Africa in an Age of Destruction.

Paid subscribers automatically receive a complementary copy and hard copies may be purchased on Amazon or Takealot.